实验室自动化与筛选协会2013亚洲会展对杨颖女士的专访

Ying Yang: Translator of Possibilities

What does a German-language undergrad with an M.B.A. have in common with a drug discovery scientist? Venturing into the unknown, says Ying Yang. She is building her career by exploring new frontiers with talented scientists and turning their discoveries into practical, profitable applications.

Ying Yang, SLAS Asia Conference and Exhibition committee member and managing director for LBD Life Sciences Limited in Beijing, China, is a natural translator. Whether interpreting a foreign language, a business philosophy or science discovery, she approaches each new project with a mind receptive to possibility. “Because I don’t immediately grasp the intricacies of science on such a deep level, my cup is empty. I can think openly and collaborate with others across scientific disciplines and business sectors,” she says.

When she was younger, she could not really imagine working in science. “I’m more artistic than techie,” says Yang, who studied classical piano for 10 years. “I work well in this area because I grasp an idea quickly and translate it into a business usage. That’s my major strength. This field opened to me. In Chinese we call it ‘yuan,’ which means destiny. It’s my destiny.” A youthful desire for independence coupled with quick-study skills for business led Yang into the science and technology industry.

She is not shy about breaking into a new area. This spirit of discovery is a strong bond that Yang shares with her scientist colleagues. “Many disciplines – science, technology, manufacturing – hold core similarities. It’s about communication, understanding high-level questions and collaborating with experts in a timely manner,” she asserts. “What our company offers can always be summarized in five minutes, if it were to be introduced to decision maker. If I can understand what I am talking about, I can help others engage in the collaboration.”

At the end of the day, regardless of what type of business she is conducting, all new proposals should answer Yang’s key commercial questions: What is it? How does it work? What are the applications? What is the unique selling proposition (USP)? To whom is this USP important? Yang analyzes the differences in competitor’s products or services and reviews a few case studies to develop that five-minute story line for new business.

Found in Translation

Yang’s undergraduate studies in German unlocked her ability to understand another culture and language while it also opened the door for her to work abroad. “Learning about a new culture helped me decide to become an independent woman while I was still in college – that is quite unusual for my culture in China,” says Yang, who studied at Tongji University in Shanghai, China.

“It is important that students don’t fence themselves on any particular path,” she recommends. “For example, I would have had fewer opportunities by deciding ‘I know German; all I can do is be a translator.’ I have had a much more colorful life than many of my classmates because I did not withhold myself from a venture into an unknown area.”

The early years of her career included many business management opportunities, which offered her a path to independence without confining her to one industry or profession. Because she knew German, she worked for the shipbuilding division of a State-owned company in China, and was assigned to various tasks of communication between peer colleagues and German shipowners. When she held this post, she worked in Hamburg, Germany for nine months. After delivering three new vessels in four years, Ying decided to explore new opportunities. This time she got her hands on entrepreneurship, setting up an IT company in Beijing. For Ying, this role was the most challenging of her career at that point. A stiff learning curve yielded great rewards in understanding teamwork, business creation, company strategy and resilience in difficult times. “What always intrigues me is that many IT companies seem to compete purely on pricing, delivery times and customer relationships and not much on innovation. My job training did not provide me with a high-level concept of how innovation could be introduced and applied,” she explains.

“This inspired me to pursue an M.B.A. at Cambridge University in 2002,” she continues. “The M.B.A. program helped me broaden my view and understand the different ways to develop business innovation,” Yang says. It was a course of study that would strongly influence her future business development and offered a fantastic year of life experiences in a cross-cultural environment, and all on a strikingly picturesque campus.

In 2003, Yang’s newly earned M.B.A. helped her land a dream job with Cambridge-based TTP Group, an independent technology development company that provides concept, design and production solutions to its clients. It is also the parent company for LBD Life Sciences. “I learned about TTP from my M.B.A. studies as it is one of the four largest technology consultancies in the U.K.,” she explains, adding that a Cambridge networking event secured the interview. “A senior TTP executive I met at an event found my background very interesting and invited me to interview with other senior executives at the company.” The company quickly identified Yang as the right person to lead TTP’s entry into the Chinese market.

In the beginning, Yang worked as a consultant and business manager for all of TTP’s China initiatives while remaining in Cambridge. The work exposed her to a broad spectrum of business development projects in science and technology. “I would say my early work experiences with TTP Group are what most support the work that I do now. It is the most valuable experience I have had,” she comments. As her work responsibilities grew, Yang acquired a deep attraction to the problem-solving process associated with science and technology discoveries.

In 2008, Yang returned to China as TTP Group’s chief representative in Asia to expand operations through TTP Labtech, a subsidiary focused on instrumentation. “My sales colleagues with Ph.D.s trained me in about two or three days and sent me back to China saying ‘good luck!’ I was the only one without a scientific degree or background,” she continues. With the primary goal to develop partnerships between customers and collaborators, Yang feels she was very fortunate to learn the ropes from Jas Sangera, managing director of TTP Labtech.

By 2010, TTP Labtech was ready for a spin off. To market and support the full range of life-science related instrumentation produced by TTP Labtech and other foreign manufacturers, the company created LBD Life Sciences Limited with Yang at the helm. Through the acquisition of another Chinese company, LBD Life Sciences added procurement and supply of reagents to its services and established offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Beijing. “Two years later, we have a very good market share in China in the pharmaceutical R&D sector and with life-science research academic institutes. We are well-known for our ability to introduce highly innovative instruments and reagent products to the Chinese market,” Yang comments.

Fluent in Business

The contrast between how business was conducted in the U.K. and how it unfolds in China interests Yang. “In more mature markets, such as the U.K., people need to think carefully about strategy and business opportunities by studying and analyzing data,” she explains. “In China everything develops and changes quickly. It is a dynamic market with lots of opportunities and uncertainties. Thus, the ability to sense the opportunity and catch the wave is important. You must have the flexibility to adapt.”

“Business as usual” in China may seem chaotic and unorganized in the eyes of Western market watchers, Yang asserts. “Typical, mature-market strategies are like swimming from point A to point B with careful planning and routing. In China one may just jump into the water first, with a vague idea to swim from point A to point B. Once in the water, one may quickly re-route upon finding that point C is a better destination due to the changing current,” she explains.

For Yang this flexible focus sharpens her eye for opportunity. And it sometimes confuses her friends, she says with a laugh. “They ask me what exactly I am doing! For example, one year I met with telecom businesses to discuss our mobile television technologies. The next year I approached medical device companies about insulin pumps!”

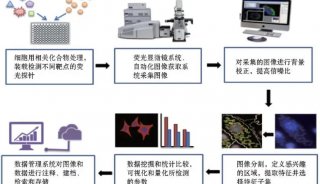

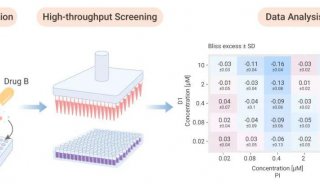

Regardless of the sector, the translation of an innovative idea for Yang is composed of capturing essential information, understanding and digesting it thoroughly, finding the answers for her key commercial questions, applying the right structure and finding the right audiences. Even with her busy schedule, she always tries to meet with those bringing collaborative petitions to LBD Life Sciences. “This is a meaningful job because our mission is innovation, not just creation,” she explains. “I would like to interpret innovative solutions to the scientific community so that we can nurture their creativity and enhance their productivity.”

Yang feels that this vision is captured in LBD Life Science’s Chinese name, Teng Quan. “Teng means ‘to leap forward’ and Quan means ‘spring’, as in water emerging from underground. The leap forward stands for innovation and the spring means to nurture quietly. I hope this attitude can be cultivated over the course of the company’s growth,” she explains.

Building Better Collaboration

Developing LBD Life Science’s teams and a corporate culture from scratch was not without obstacles, Yang observes. “In any growing venture, you will come across similar obstacles. Competition, income, developing teams and varying leadership skills to inspire them are quite usual for almost every set up to a certain point. We are lucky. We are steadily growing,” she says. She credits their success to the collaborative team-building efforts of individual company members. Her adaptable leadership skills she owes to her early experiences at TTP, which spanned many different areas of IT – printing, business products, telecom, medical devices and life science instruments.

“We came into the Chinese market with perfect timing, when pharmaceutical R&D activities started to seriously take off,” Yang adds. “I think we started off strong, even when no one knew about our company. Now almost everyone in the drug discovery area knows us.” She credits this to first having great products, but also backing it up with a great attitude. “We determine what our customer expects and deliver on our promises,” she states.

Another reason for the company’s good reputation is the team’s leverage of what it calls the partnership and community approach, which includes working after hours to build the company’s image. “Using this approach, I became active in SLAS and also began hosting a monthly ‘TGIT (Thank-God-It-is-Thursday) wine party for drug discovery professionals,” Yang explains. “We found it is useful to set it on Thursday rather than Friday, when most people may have personal commitments. We helped people to know us using this word-of-mouth approach. This is also a very useful platform for peer colleagues to catch up and get to know new faces in a relaxing and enjoyable social networking platform. It also shows our commitment to contribute to knitting a social network for this community.”

What the team earned together through its efforts is top ranking in main instrumentation within the drug discovery community in their respective product categories. Considered pioneers in the creation of the supply and procurement management model to serve the life science community in China, the LBD team’s next goal is to extend its innovation-enabling technology to more translational medical science and to expand into more diagnostic, patient-side applications. “We believe that several of TTP Labtech’s products have great potential,” Yang asserts. “I welcome people who work in this area to be in concert with us.”

Bridging Science and Art

While her former linguistics classmates may have a difficult time imagining Yang in the scientific field given her passion for languages and music, Yang considers it a fine line between science and art. “I think scientists understand that science is an art. They go together. Sometimes science may be too narrowly defined? There is not much of a border between the two,” she observes.

Pursuing art is something she has little time for, but strives to include in her busy life. Extensive business travels require Yang to cultivate solitary pursuits – reading, music and sightseeing – that easily fit her schedule. “It’s tiring after all the work, and I don’t have much time,” she says, explaining that she relies on her skills as a fast reader to consume books that interest her. Solo business travel allows her to be spontaneous about visiting local gardens when her travel plans change at the last minute. She describes these scenic tours as restful and calming. “I appreciate nature. It’s the best way for me to stimulate my thinking and relax,” Yang comments.

Expanding SLAS in Asia

Yang’s SLAS involvement developed when a client colleague reached out for help in organizing the first SLAS Asia conference a few years ago. “He needed to invite someone who understood the organizational and logistical aspects of business planning. They pulled me in because most of them were either abroad or just too busy. I was the only one in China and seemed to be the only one that had time. There was not a team here at that time. Together with the first committee members, we went to find the first venue, talked to different organizers and helped broadcast the message,” she explains.

As a member of the SLAS Asia Conference program committee, Yang enjoys networking and helping others connect in SLAS. “A lot of co-chairs and people I invite to chair sessions are really focused and busy professionals, but they commit their time to contribute to the conference and the community. This demonstrates how close and supportive the SLAS community is. We eagerly anticipate that the membership in China will continue to grow. SLAS offers a platform where drug discovery professionals can meet new friends and old and discuss and collaborate on the potential of the latest break-through they have achieved.”

Her many experiences at SLAS events – including serving on the local committee for the First Annual and the program committee for the Second Annual SLAS Asia Conferences and Exhibitions – led her to further opportunity as program committee member for the Third Annual SLAS Asia Conference and Exhibition to be held June 5-7, 2013, at the Grand Hyatt Shanghai. Yang also participated in the SLAS2013 Innovation Award selection process as a judge; she will co-chair the Asia session that will host four SLAS2013 Innovation Award finalists in Shanghai.

“SLAS Asia is a very well organized conference,” Yang says. “Most of the attendees I have talked with gained something by attending. Some learned more from the disease-focused sessions, whereas others got more out of the technology review and connecting with speakers. People generally have found the vendor exhibition and tutorials very useful to collect valuable information at one event.”

Yang describes the drug discovery community in China as small, but poised for rapid expansion through SLAS. “With SLAS, I hope we can draw in more people to build the community,” she concludes. “We can find projects for collaboration.”